During the early days of the COVID 19 pandemic, I was at home writing my new book The Projection Designer’s Toolkit . One of the few perks of the complete shutdown of our industry was that we all had a lot of time on our hands, and it allowed me the opportunity to engage in a series of interviews with some of the top names in our projection / media design field. I was lucky enough to interview dozens of different designers, programmers, engineers, and assistant designers as part of my research. Many of these interviews found their way into the book as a collection of field notes, giving the rare opportunity to see a snapshot of the state of our industry in this moment of time. As is often the case in publishing, some of this work had to be omitted due to boring things like layout, page constraints, and deadlines. This week, I am happy to share with you one of these wonderful interviews that unfortunately could not be included in the printed text. This interview, with Jared Mezzocchi, covers a wide range of information from his background, to his work with students at the University of Maryland, Jared’s ground-breaking work of creating live theatre presented on virtual platforms, the connection between directing and design, and much more!

Jared Mezzocchi is an Obie award winning director and multimedia designer, playwright, and actor. Mezzocchi’s work has spanned all throughout the United States at notable theaters such as: The Kennedy Center, National Sawdust, Arena Stage, Woolly Mammoth (company member), Cornerstone Theater, Portland Centerstage, South Coast Rep, HERE Arts, and 3-Legged Dog. In 2016, he received The Lucille Lortel and Henry Hewes Award for his work in Qui Nguyen’s Vietgone at the Manhattan Theatre Club. In December of 2020, The New York Times highlighted his multimedia work on a list of the top 5 national artists making an impact during the pandemic. His work was also celebrated as a New York Times Critic Pick on Sarah Gancher’s Russian Troll Farm (Co-Director & Multimedia Designer) where it was praised for being one of the first digitally native successes for virtual theater. Currently, Jared is creating a new work through his mini- commission at The Vineyard Theatre in New York City entitled On the Beauty of Loss. In addition to this, he is writing a new book, A Multimedia Designer’s Method to Theatrical Storytelling, which will be released through Routledge. He is a two-time Macdowell Artist Fellow, a 2012 Princess Grace Award winner, and spends his summers as Producing Artistic Director of Andy’s Summer Playhouse. Outside of his artmaking, Jared is an Associate Professor at The University of Maryland and the CEO of his production company, Virtual Design Collective (ViDCo).

As a theatre artist, your work stretches across a number of disciplines from projection design, to directing, and playwriting. Tell us a bit about your background and how you came to have such a multifaceted career?

I started as an actor when I was very young and continued acting well into my time in NYC. It was the end of high school when I picked up a video camera and started to edit short films together for assemblies. When I got to Fairfield University as an undergrad, I double majored in Theater and New Media: Film. As a theater major, I studied acting and directing with a few courses in playwrighting. As a film major, I studied writing, filming, editing, and directing. My sophomore year I started to explore how to incorporate my film work into my theater work and by senior year had written and directed a full-length multimedia production called The One Stoplight in Hollis which was about the loss of my father during the same week my sister had a baby. The production had pre-filmed sections that actors jumped into. The stage was a purgatory while the 3 screens were 3 different cameras angles of a singular memory. Back in 2007, this was operated off of 5 DVD players that were all sync’d up.

This production got me accepted into the MFA program at Brooklyn College in 2007, for a degree in Performance and Interactive Media Arts (PIMA). There I learned coding and programming for live events as well as a depth of education in performance art of the mid-twentieth century.

While in school I was hired as a Video Programs Designer with Big Art Group, while simultaneously a Projection Designer at a club in SoHo called Santos Party House, owned by Andrew W.K. In both of these jobs, I was exposed to performance art and live video manipulation for immersive events. I took all of that improvisational and experimental practices back into traditional theater making and have been shapeshifting as a director, writer, and designer whenever I see a great opportunity to explore multimedia in live performance. I am actually about to return to acting with my upcoming new work SOMEONE ELSE’S HOUSE, at the Geffen Playhouse. This is about a haunting story from my family’s past, which I am writing, designing, and performing.

Over the last decade I have been hired as Artistic Director of Andy’s Summer Playhouse, the children’s theater I grew up performing in. I also am an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland in their MFA Design program. These employment opportunities have shifted my goals as an artist to include making space for other experimenters and disruptors of traditional performance.

I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed being within a category. I get bored when I find myself replicating the same process of artmaking, and so flipping my discipline is a way of expanding my muscle as a total artist. By changing my discipline, I constantly interrogate processes of generating work, which informs other disciplines I will ultimately return to. Particularly, though, I love live performance. As a filmmaker I was never satisfied with having anything “in the can” as they say. Placing multimedia into live performance is a commitment to mortality, I believe. It stems back to losing my father while in college. To be able to write, direct, design, and mentor allow me all of the opportunities to explore a form that I love so much.

I know you head up the Projection Design program at the University of Maryland, College Park. What are the important skills that you are drilling into your projection design students and in what way do you find teaching informs your own work as a designer?

To be as fast as a lighting designer and as agile as an actor! By this, I simply mean you have to know how to collaborate in real space and time with your collaborators. To me, being a good designer is knowing what tools are most effective for your artistic vision and mastering the needed techniques for that specific design to be flexible in the space so that a collaborator can be inspired by what you are delivering and simultaneously be invited to shape the event with you in real time. It’s like acting, in a way. You have to know how to arrive equipped for the scene and you have to have the technique to listen and respond in real time to the tactics that your scene partners are engaging you with.

Be as fast as a lighting designer and as agile as an actor!

Jared Mezzocchi

Like acting, technique is an ever-growing muscle. So to have an opportunity to exercise that muscle in a classroom is really exhilarating to me. I also hold my classroom like I would a collaboration lab, where everyone in the room has equal footing and we are all investigating unknowns.

Secondarily, like acting, I have my students think of their design like a scene partner. Like any actor would prepare, the choices must have a super-objective (an overall “want” throughout the show), objectives (“wants” within each scene that help you get closer to achieving your super-objective), and tactics (actions within each beat of a scene that actively pursues your objectives and super-objectives). When you start to create desire and intention for your design, that breathes life and response through the actions onstage, you will inevitably find theatricality and dramaturgy within your design.

Since the COVID pandemic put everything on hold for so many theatres and theatre artists, many projection and media designers shifted towards creating online performances. I know you did a lot of experimentation and research around media tools for creating live online performances. Your production of Russian Troll Farm, which you co-directed and designed,was particularly well-received as an exciting new foray into this realm. Can you tell us a bit about your work in this area and how it might affect your future work?

With all of the work since the COVID Pandemic, I have committed myself to exploring what it means to be creating live on a virtual platform. With my first few projects, like Russian Troll Farm in October 2020, and my very first project She Kills Monsters in May 2020, we generated all of the work live and performed it live to a viewing audience. With She Kills Monsters, we performed it once and had nearly 5,000 viewers tune in. In that performance, we livestreamed the zoom meeting in gallery view and coordinated the actors to turn on and off their cameras, as well as use custom built snap camera filters that supplied masks, foreground overlays, and backgrounds. This show is about Dungeons and Dragons and served the zoom aesthetic really well.

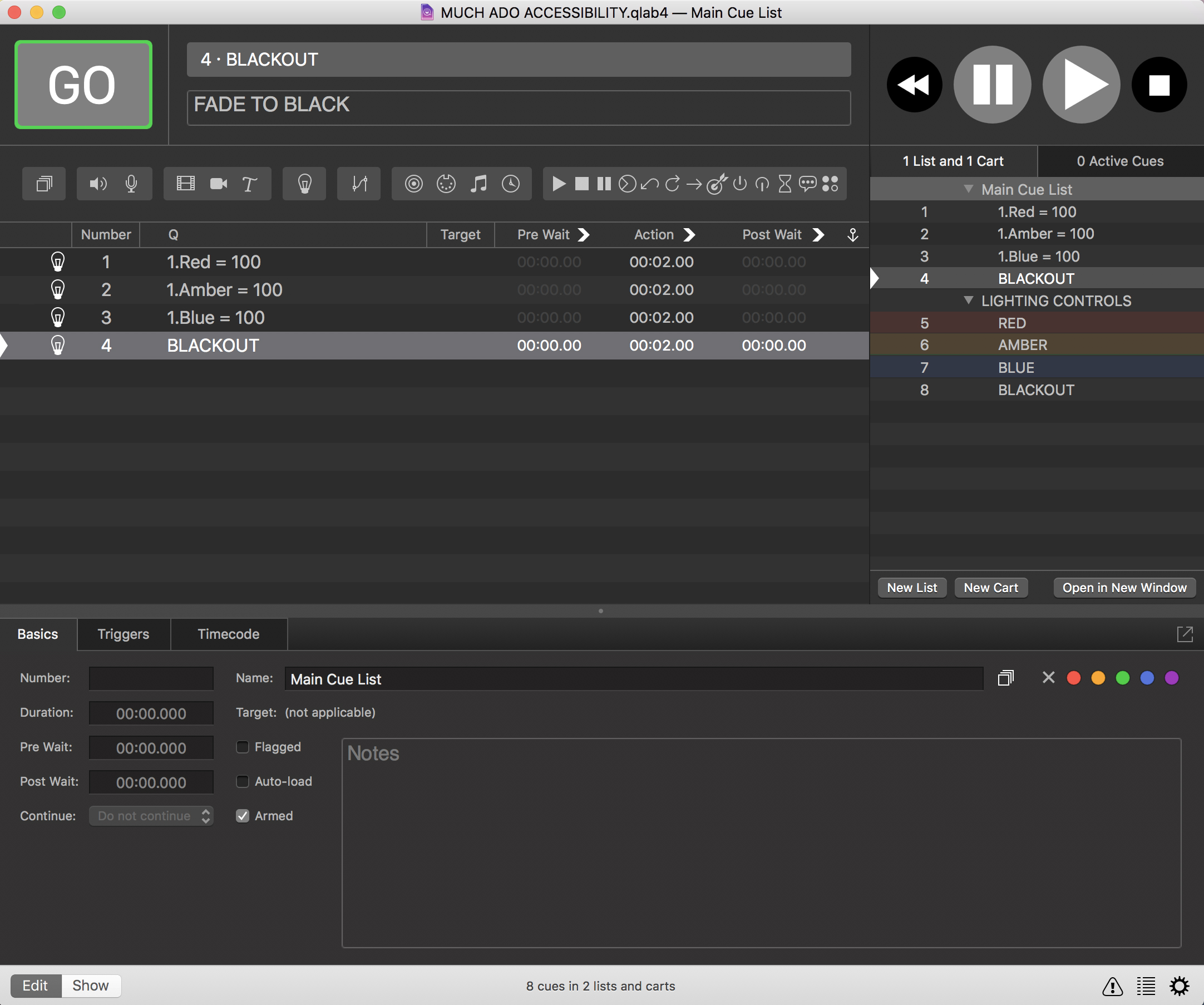

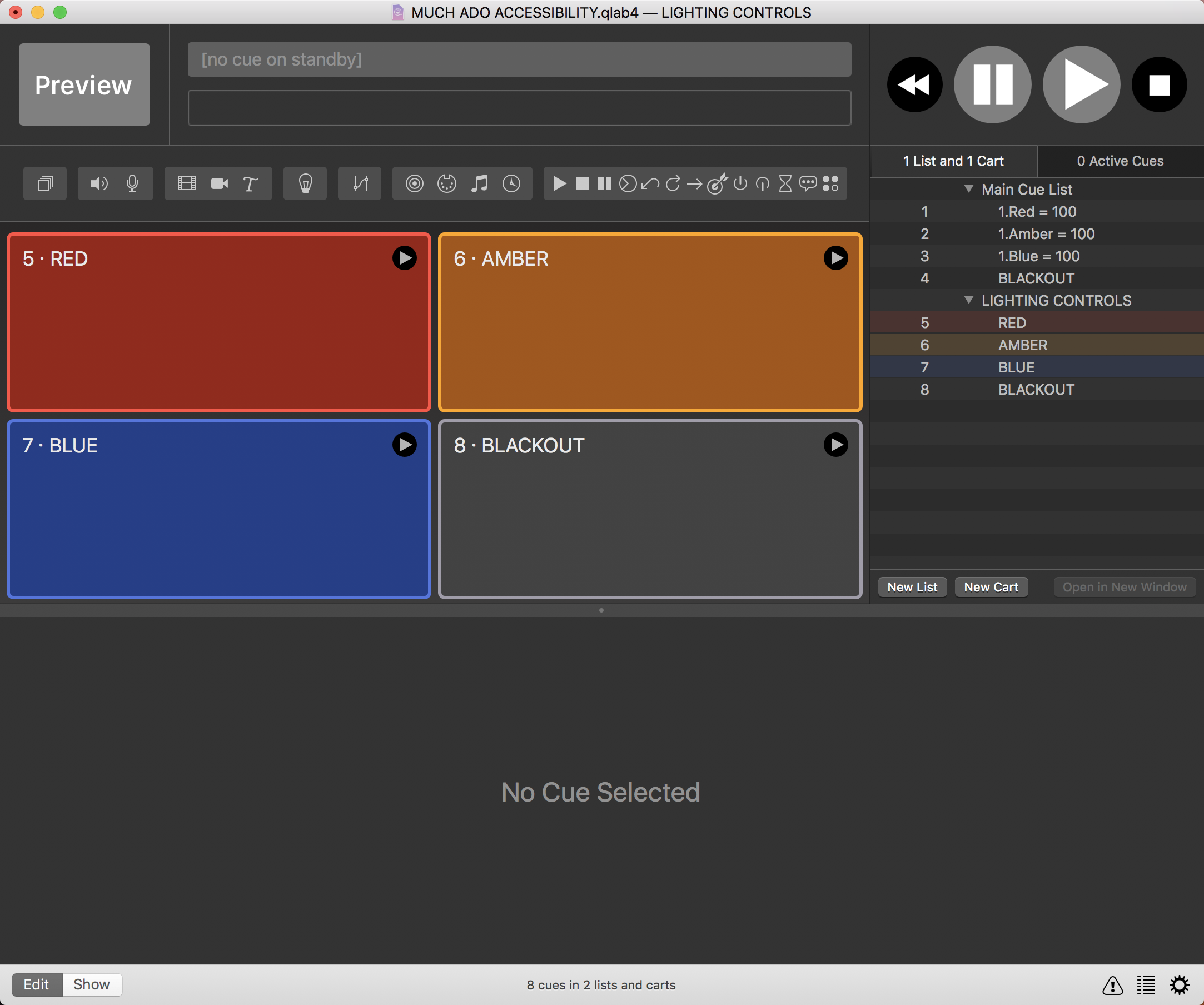

With Russian Troll Farm, I wanted to take it a step further and implement the software Isadora into the performance. For this, I didn’t want the viewer to feel like they were on zoom or that the actors were using zoom as their stage. This required a lot of cinematic and television research and development within Isadora. In time, we created a live cinema event that utilized thousands of video cues, many of which were operated like a TV studio. We held the actors in a gallery view on zoom and used Isadora to screen grab each of their zoom boxes and mixed them together into one cinematic composition in Isadora. This allowed us to place actors in the same space, cut between several shots, as well as create montages with overlays of pre-filmed video alongside live performers in real time. Because of its complexities, I ended up operating the show’s video design during all 5 live performances. It felt more like a conductor with their orchestra because I would cut the scenes differently every night, following the actors’ energies. If I saw one of the actors exploring a response to something differently, I may choose to cut to their reaction a few more times to track the humor of it. It was exhilarating and live and totally responsive to the performers telling the story.

Since then, I’ve also explored filming sequences in real-time, adding effects to the performance in post-production. In these circumstances, I would commit myself to a one-take with the actors, so that the edit wasn’t augmenting the actors’ singular performance, but instead adding a little extra style to the stream of it. I might not have thought of this as live back in May, but I definitely feel the liveness when watching and intuiting that the actors are performing that scene without stopping. The term “Liveness” has sort of re-invented itself to me during this time.

It may come across as stubborn, but I believe myself to be a theater researcher, first and foremost, and I believe that a defining factor of theater (as opposed to film or tv) is that our storytellers tell their tale without stopping. By committing to that fact, it forces the entire creative team to strategize very differently than making a film. All solutions must be in real time. And I’ll tell you, the fear in most producing organizations is PALPABLE. It seems like everyone is afraid of doing anything live online. They fear the seemingly insurmountable number of variables that could fail the endeavor. Then comes along a few organizations that believe in it, and those are the organizations I want to celebrate right now. This is not the time to be a low-budget film studio. This is the time to scream to the masses that being alive is a challenging thing, and yet here we are and we are proud of that mortal fact. I think the fear of failure is completely valid, but – to me – that makes me want to double down and still leap into the theatrical abyss to see our techniques come alive. Theater has survived so much for so long, it seems only natural to challenge the form at its core right now. So many unexpected outcomes could occur in this experimental moment. In every project I’ve worked on I’ve learned something new about theater and community building and liveness.

I’ve even worked to design a memorial with 700+ visitors who joined a Zoom to celebrate the life of their friend and colleague. We built several breakout rooms with slideshows and guest books and film screenings. We had a live eulogy with the family in the main zoom room, which used Isadora to live design their service. We had family visitations for friends to catch up. We had private breakout rooms for long lost friends to bump into each other and have private space to catch up. The theatricality of such a digital space was SO enlightening to me and taught me so many essentials to caretaking for an audience. I will never take ushers and front of house staffers for granted EVER AGAIN!

All of this is to say that this time period has greatly impacted me as an artist. When in a theater space, there is no negotiating. It must happen without stopping. Here in the virtual space, you have a choice, and so it really makes you interrogate the form of theater and what makes it essential to the human condition. Again, at its essence, theatre is a celebration of mortality, not a fear of it. Film, TV, and other digitally made forms, are more of an immortal identity. They get created and can be distributed in that exact form, forever. Those forms have an art object that is distributable. Theater does not, it is temporal and is created and consumed at the same time. This, to me, amplifies the impossible dream of theater making. It’s so challenging, and yet we do it. It tells us that we, humans in constant decay, can still create something powerfully composed, intentionally live, and eternally memorable. That’s legacy making, at its best. Coming out of the pandemic, I am more certain than I’ve ever been that theater is my native form as an artist. I couldn’t be more committed to it than right now.

What are some tools or processes that you use to get from the idea stage to communicating your design?

Live tests. I’ve struggled for years to pre-visualize through storyboarding. This has been a real challenge for me in collaborations. It’s not that I didn’t prepare them, but instead I would become frustrated that the idea is not conveyed correctly in a still image on a computer screen or printed page. Through this struggle, I have been able to name that what I think I offer most is not in the content, but in the form and function of the design.

This goes back to what I teach: Super-objectives, Objectives, Tactics. If a scene isn’t working with the actor, you don’t cut the scene. You dig deeper into the character analysis and conflict and tactics being used between the scene partners. Similarly, with design, I don’t want to get to the tech rehearsal and see that a piece of content doesn’t work and therefore gets cut. Instead, I want to acknowledge the content isn’t fulfilling the objectives and tactics agreed upon during the pre-production process. In exploring these concepts, it’s less of a binary conversation about the cue. It’s no longer a cut/keep dialogue, but instead a re-commitment to the objectives and character development of the media so that the team can sculpt new content to increase the efficacy of the media’s presence and intent onstage at that moment.

Therefore, my most effective moments are doing live tests prior to the tech rehearsal. Just like actors in a rehearsal room trying out different ideas and observing how their actions rev the engine of the story or stall it, I want to experience that with design too. This also is the language of your director and collaborators. I find when I start speaking in media terminology, it becomes a foreign language with the team. It is our duty as multimedia creators to learn the language of the form. Sit in on rehearsals and learn how your director and actors are speaking to each other about the conflicts and characters of the play, and start to craft your own language in the same way when speaking of media.

Yes, I still pre-visualize my work and send samples to my collaborators, but I have grown to put significantly more currency in the objectives and intentions of my media-as-character. Why does media enter? What does media want when it is on stage? Does it get what it wants? How is it responsive to the actions on stage? Why does it exit? Sure, tactics will involve media-centric ideas like saturation, speed, blur, scale, angle, composition, etc., but these are the tools of the media, just like costumes and props are the tools of the actors. Everything must have a reason to be on the stage and exist in the manner it exists. Using this language will only solidify its reasons, and therefore clarify its impact to the total work of art as a member of the ensemble.

You have a background in directing and playwriting, as well as design. In what way do you find that these experiences shape your collaboration and workflow?

Each of these roles has a different proximity to and control of the live event. I love how playwrighting is an exploration of the interior of a play’s design, written months and years before it plays out in real time. I love how directing is an exploration of delegating and inspiring visual design to others from a seat in the house, observing its life in repetition over the weeks of development leading up to its emergence. I love how design is a singular journey in the trenches of storytelling that has significant impact on the stage picture being consumed by the audience. Each of these disciplines offer me a vastly different perspective of the live event as a temporal art object. Not one role can see all of its parts, so to have the opportunity to constantly shape-shift my role as a multimedia creator, it has helped me remain agile. As the community of theater-makers continue to evolve ideas around how to incorporate multimedia into the theater, sitting in each of these chairs helps me evolve my collaborative vocabulary and tactics in real-time as well.

Many of the works in your résumé are world premieres. Can you talk a little about the process of working on a new script? In what ways does it differ from designing a previously produced script? How does the playwright factor into your process?

I love working with playwrights because I think the total-process-of-theater-making involves the development of the script. It’s the forming of a band, and I just am super inspired when the songwriter is within the group. It’s also just so invigorating to be in a room where literally no one knows if the thing we are creating will work. That’s a type of risk that teaches me how to be a better human. Making previously produced scripts also can produce that type of risk too, especially when the team is completely re-inventing the form in which that script is being produced. This isn’t intending to be a comparison at all. But making new work with a playwright in the room gives an added thrill of re-arranging scenes, writing an entirely new act during previews, or even completely changing the ending. I love being a part of that type of process because you also get to examine really great ideas that just don’t work dramaturgically for that particular show. That sort of experimentation deepens my toolkit exponentially.

One of your projects, How to Catch a Star, was an adaptation of the Oliver Jeffers book that you wrote and directed for the Kennedy Center. This production featured projection design as a heavy component, designed by Olivia Sebesky. Do you find the collaborative process to be different when you aren’t designing (especially on a media-heavy production)? To what degree do you find yourself involved with the projections (or do you purposefully try to distance yourself a bit)?

Well I think it’s important to name that The Kennedy Center provided us several workshops leading up to auditions and rehearsal. These workshops were for whatever I needed as a writer/director. So I asked to bring in my choreographers, Matt Reeves and Colette Krogol, my composer, Zak Engel, and my projection designer, Olivia Sebesky into a room to devise our sandbox of play. This was before the script was even written. In these initial workshops, we collaborated as co-creators trying to understand the architecture of how we would tell this story. As writer/director, I led with a series of goals and personal impulses that were imperative to the creation of this work. Of course, we also had the book as a skeletal outline but a part of my imperatives was to incorporate characters from several Oliver Jeffers’ books too. So we were blending a bunch of narratives together within a mostly non-verbal journey of body, image, and sound.

To use the band analogy again, those workshops felt like jam sessions. We each had our instruments and were finding our rhythms and crescendos and naming who was leader/follower within every section of the piece. In those sessions, I found myself more as a writer than a director so that there wasn’t as much of a hierarchical power dynamic and instead I was writer-as-scribe, collecting all of the most inspired impulses to embrace when going away to write the actual script. As I fleshed out the scenes, the DNA of everyone’s impulses were inevitably a part of the architecture.

This type of rehearsal room is my dream as a director. It allows for collaboration to be less sequential (I have the idea, and you produce the idea) and more conversational (I have a goal, and let’s all establish collective strategies for achieving this goal together). So in a way, it wasn’t just that I was involved with the brainstorming of projection design with Olivia, but instead all of these collaborators, Olivia included, were invested in establishing the story together. This allowed Olivia to not only bring images to the table inspired by the story I was writing, but also allow me to embrace her discoveries within her own process that could evolve the story in unexpected ways.

I want to build a room that helps leverage designers like Olivia to lead with her own impulses as well and let that inspire the total work of art. By using those initial workshops to establish the architecture of our storytelling, we essentially built a sandbox that had specific boundaries to where we were most compelled to tell our story visually. Then Olivia’s virtuosic talents could improvise within the form and find her own sense of play. Because of the boundaries set at the beginning, the band was able to sustain a jam session throughout the entire process without feeling like we were in our own silos of creativity.

I don’t think I can ever turn off my impulses as a projection designer, and I would be foolish to tell my collaborators that I would do so. I also think our shared understanding of what is possible within multimedia design served as a major strength to the collaboration. That was true in not only the successful moments, but also collaborating together to overcome moments that weren’t quite landing yet. We both were able to see the visual hurdle and come to a solution together. Therefore, everything on that stage was a collective effort that utilized the best of each collaborator’s skills. Olivia Sebesky created some of the most stunning images that I only began to imagine were possible when writing it on the page. I firmly believe that the story held those images so effectively simply because we all collectively nurtured the entire journey together, from its first word on a page through to the final bow.